Redefining Parkinson’s: The Shift Toward a Biological Diagnosis

.png)

Did you know that Parkinson's disease is the fastest-growing neurological disorder worldwide, affecting over 10 million people?

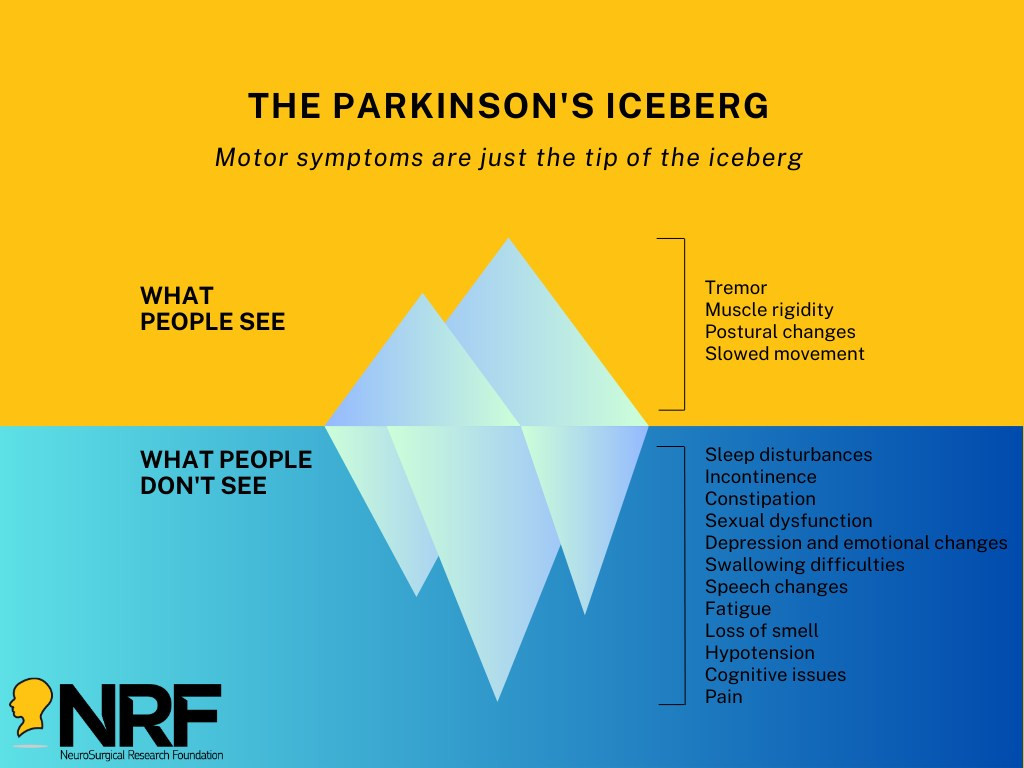

Parkinson's is a progressive, degenerative condition of the central nervous system with no known cause and no cure. While many are familiar with its movement-related symptoms, Parkinson's also presents significant non-motor challenges that severely impact quality of life, including cognitive impairment, speech difficulties, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances.

-

In Australia alone, over 200,000 individuals are living with Parkinson's, with 37 new cases diagnosed every day.

-

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) significantly raises the risk of developing Parkinson’s later in life—56% for mild TBI and 83% for moderate to severe TBI.

-

Parkinson's is more than just a movement disorder; it's a multi-faceted condition that affects every aspect of life.

Your support can make a difference in the fight against Parkinson’s. Donate today to the Parkinson’s Disease Research Appeal and help us advance critical research to better understand, treat, and ultimately cure this devastating disease.

.png)

Today on World Parkinson’s Day, the we want to turn the spotlight towards awareness, advocacy and action. For researchers at the University of Adelaide, it’s also a moment to reflect on what’s changing and what comes next.

For decades, Parkinson’s disease has been diagnosed by what can be seen: tremors, muscle stiffness and slowed movement. But by the time these symptoms appear, the underlying brain damage is already significant and often irreversible.

“By the time someone is showing motor symptoms, around 60 percent of the brain cells that produce dopamine are already lost,” says Associate Professor Lyndsey Collins-Praino, Head of the Cognition, Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disease Laboratory (CANDL). “That’s a huge hurdle for effective treatment. ”

That challenge is driving researchers to rethink how Parkinson’s is diagnosed. Instead of waiting for visible symptoms, they’re working to build a clearer, biology-based framework that helps identify the disease much earlier and supports clinicians to make more confident decisions sooner.

Over the past decade, scientific understanding of Parkinson’s has shifted from a purely clinical definition to one grounded in biology. Biomarkers — measurable biological signals found in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, imaging or genetics — are now being proposed for use to track the disease, even before outward signs appear.

“In Alzheimer’s, a biological definition using biomarkers helped advance diagnosis and pushed the field forward,” says Assoc. Prof. Collins-Praino. “We’re now seeing that same momentum in Parkinson’s.”

The next step is making those research insights usable in real-world healthcare settings.

“Ultimately, we want to build something that medical professionals can actually use,” explains Angus McNamara, research fellow. “A structured, evidence-based system that helps them recognise early risk factors, whether that’s subtle cognitive changes, mood symptoms, sleep disturbances or underlying biological changes.”

Rather than relying on a single test, this future framework would pull together multiple layers of information — patient history, symptom patterns, imaging results and biomarker data — to support earlier referrals and more targeted follow-ups, even before a formal diagnosis.

The aim is to take the guesswork out of those early, uncertain stages. A more defined framework could also help reduce misdiagnosis, which currently affects around one in five people, and separate Parkinson’s from other related conditions that need very different treatment approaches.

“We want to get to the point where a GP sees a patient with non-specific symptoms and says, ‘There’s enough here to explore further,’” McNamara says. “That doesn’t happen consistently today, but it could.”

Other health conditions, like stroke, have benefited from clear and simple frameworks that encourage early recognition and faster action. Parkinson’s needs something similar, though researchers say it must be more nuanced and grounded in biology to reflect the complex nature of the disease.

“There’s real potential here to create a scalable, proactive approach to diagnosis,” says Collins-Praino. “Not just for specialists, but for GPs and frontline clinicians, who are often the first point of contact.”

Research is now focused on identifying which biomarkers are most reliable, how they evolve over time, and how they might predict a person’s individual risk. By combining this information with AI and machine learning, the team hopes to build tools that not only diagnose, but also map out how the disease may progress for each person.

It’s a major shift, from reactive treatment to proactive identification, and one that could significantly improve patient outcomes.

“Early action makes all the difference,” says Collins-Praino. “And it starts with giving clinicians a clearer roadmap to follow.”

This World Parkinson’s Day, that roadmap is coming into sharper focus, helping researchers and clinicians work towards a future where Parkinson’s is recognised earlier, managed better, and faced with greater confidence.